Beers Criteria Medication Safety Checker

Check Medication Safety for Elderly Patients

Enter a medication name to see if it's potentially inappropriate for patients over 65 according to the 2023 Beers Criteria.

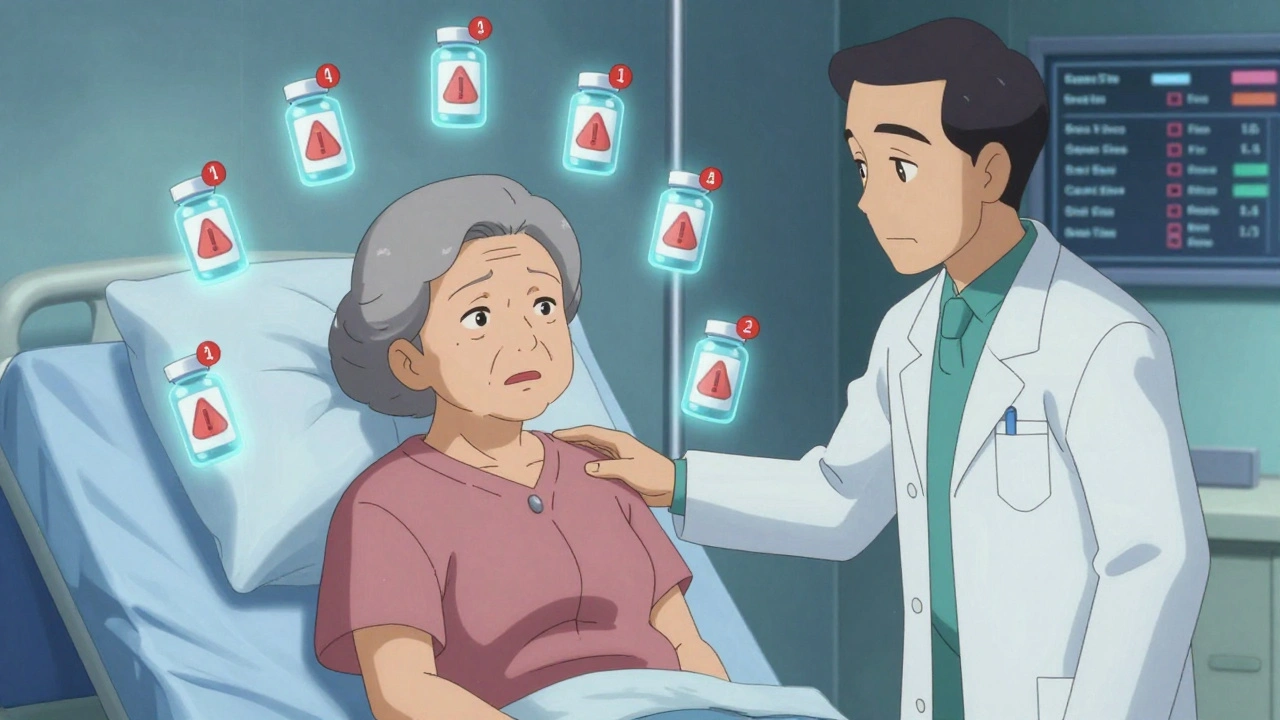

Every year, more than 1 in 3 hospital admissions for people over 65 are caused by medication problems. Not because they didn’t take their pills, but because the pills they were given were the wrong ones - or too many of them. This isn’t a rare mistake. It’s a systemic issue built into how we treat older adults. The truth is, what works for a 40-year-old can be dangerous for an 80-year-old. And yet, many doctors still prescribe the same drugs the same way.

Why Older Adults Are at Higher Risk

As we age, our bodies change. Kidneys slow down. Liver function declines. Fat replaces muscle. These changes mean drugs stay in the system longer, build up to toxic levels, and interact in unpredictable ways. A single dose of a sleeping pill that’s fine for a 50-year-old can send an 80-year-old into confusion, falls, or even coma. That’s not an accident - it’s predictable.On top of that, most older adults take multiple medications. The average person over 65 is on five prescriptions. One in four takes ten or more. This is called polypharmacy. And it’s not always necessary. Many of these drugs were prescribed years ago for conditions that have since changed or disappeared. But no one ever stopped them.

Studies show that when older adults are given potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), their risk of hospitalization jumps by 91%. They’re 60% more likely to lose mobility. And they’re 26% more likely to have a dangerous reaction - even if they’ve taken the same drug for years. The more PIMs they get, the worse it gets. Each extra one adds risk, not benefit.

The Beers Criteria: The Gold Standard for Safe Prescribing

In 1991, the American Geriatrics Society created a simple tool to help doctors avoid these mistakes. It’s called the Beers Criteria. Today, it’s the most cited guide in geriatric medicine, with over 1,200 research papers referencing it. The latest version, updated in 2023, lists 139 drugs or drug classes that should generally be avoided in older adults.These aren’t random guesses. Each one is backed by clinical data. For example, benzodiazepines like diazepam and lorazepam - once common for anxiety or sleep - are now flagged because they cause dizziness, falls, and memory loss in seniors. Anticholinergics, used for overactive bladder or allergies, are linked to dementia risk. NSAIDs like indomethacin and ketorolac can cause kidney failure or stomach bleeds in older patients. Even aspirin, long thought to prevent heart attacks, is now restricted for primary prevention in people over 70 because bleeding risks outweigh benefits.

Some updates are specific. Tramadol, once considered safe for pain, is now listed because it can trigger dangerously low sodium levels - especially when mixed with diuretics or antidepressants. That’s not a side effect. It’s a known, measurable danger. And it’s preventable.

What makes the Beers Criteria powerful isn’t just the list - it’s how widely it’s used. Epic, the biggest electronic health record system in the U.S., now triggers automatic alerts for these drugs in 87% of its geriatric installations. When a doctor tries to prescribe a flagged medication to a 75-year-old, the system pops up a warning. That’s a big step forward.

The Missing Piece: What to Use Instead

But here’s the problem. Telling doctors what not to prescribe isn’t enough. Many don’t know what to prescribe instead. That’s why, in July 2025, the American Geriatrics Society released something new: the Beers Criteria Alternatives List.This isn’t just a list of safer drugs. It’s a practical guide to non-drug options too. For example, instead of giving a sleeping pill for insomnia, the Alternatives List suggests cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) - a proven, long-lasting fix that doesn’t cause falls. For chronic pain, it recommends physical therapy, heat, or acupuncture before reaching for opioids. For urinary incontinence, pelvic floor exercises beat anticholinergics every time.

Out of 47 recommended alternatives, nearly 40% are non-pharmacological. That’s a game-changer. For years, doctors felt stuck - they knew a drug was risky, but had no clear alternative. Now, they have options. And those options are backed by real evidence, not guesswork.

How Hospitals Are Making It Work

Some places are turning this knowledge into real results. At the Mayo Clinic Rochester emergency department, a team of pharmacists, geriatricians, and ED doctors worked together for six months to redesign how medications are handed out. They trained staff, rewrote protocols, and added pharmacist-led medication reviews before discharge. Within six months, they cut potentially inappropriate prescriptions by 38%.At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, they focused on medication reconciliation - going through every drug a patient was taking before admission and deciding what to keep, stop, or change. Their 30-day readmission rate for medication-related problems dropped by 22%.

These programs didn’t happen by accident. They required training, time, and resources. Most successful teams include at least one clinical pharmacist with geriatric certification. They spend about 0.5 full-time equivalent per 20,000 emergency visits. That’s not expensive compared to the cost of a single hospital readmission, which averages $12,000.

But not every hospital has the staff. Rural EDs, in particular, struggle. Only 31% have full geriatric medication safety programs, according to the National Rural Health Association. And even where systems exist, alert fatigue is a problem. In one survey, 65% of doctors ignored Beers Criteria warnings because the system flagged everything - even safe drugs like warfarin for atrial fibrillation. That’s why the AGS is working on AI-driven alerts that understand context, not just age.

What Patients and Families Can Do

You don’t have to wait for the hospital to fix this. If you or a loved one is over 65 and taking multiple medications, ask these questions:- Why am I taking this drug? Is it still needed?

- Is there a non-drug option I could try first?

- Could this interact with my other meds or health conditions?

- What happens if I stop it? What if I keep taking it?

Bring a full list of everything you take - including over-the-counter pills, supplements, and creams - to every appointment. Ask for a medication review at least once a year. If your doctor doesn’t know the Beers Criteria, ask them to look it up. It’s free and publicly available.

Don’t assume that if a drug was prescribed years ago, it’s still right. Bodies change. Conditions change. So should your meds.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Now

By 2030, 21% of the U.S. population will be over 65. That’s 74 million people. And 1 in 3 of them will be hospitalized because of a medication problem. The cost? $528 billion a year. That’s not just money. It’s lost independence, broken hips, cognitive decline, and early death.Medicare and Medicaid are starting to act. CMS now requires emergency departments to track medication safety under Measure 238. Hospitals that fail to meet standards face reimbursement cuts. That’s pushing change.

But real progress won’t come from rules alone. It comes from doctors who listen. Pharmacists who ask questions. Families who speak up. And systems that don’t just warn - but guide.

The tools exist. The evidence is clear. The question isn’t whether we can do better. It’s whether we will.

What are the most dangerous drugs for elderly patients?

The most dangerous drugs for older adults include benzodiazepines (like diazepam), anticholinergics (like diphenhydramine), NSAIDs (like ketorolac), and certain opioids (like meperidine). The 2023 Beers Criteria also added tramadol due to its risk of causing low sodium levels, and restricted aspirin for primary heart disease prevention in people over 70. These drugs increase fall risk, confusion, kidney damage, and bleeding. Many are still prescribed routinely, even though safer alternatives exist.

Can elderly patients stop taking medications safely?

Yes - but only under medical supervision. Stopping a drug suddenly can be dangerous, especially for antidepressants, blood pressure meds, or seizure medications. The key is deprescribing: a planned, gradual reduction based on the patient’s goals, health status, and risk factors. The AGS Alternatives List provides guidance on how to safely stop certain drugs and what to replace them with. A clinical pharmacist or geriatrician should lead this process.

What’s the difference between Beers Criteria and STOPP/START?

The Beers Criteria focus on identifying potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) to avoid. STOPP/START does both: it flags inappropriate prescriptions (STOPP) and also identifies important medications that are being missed (START). For example, STOPP might flag a benzodiazepine, while START might remind the doctor that the patient needs a statin for heart disease. Together, they give a fuller picture of prescribing quality.

How do I know if my elderly parent is on too many drugs?

Signs include confusion, dizziness, falls, memory problems, constipation, or sudden fatigue after starting a new drug. If your parent takes five or more prescriptions, especially if they’ve been prescribed by different doctors, it’s time for a medication review. Ask for a pharmacist-led assessment. Bring all pills - including vitamins and OTC meds - to the appointment. Don’t assume everything is still necessary.

Are there non-drug options for common elderly conditions?

Yes, and they’re often more effective. For insomnia, try cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-I). For chronic pain, physical therapy, heat, or acupuncture work better than opioids. For overactive bladder, pelvic floor exercises reduce symptoms without side effects. For anxiety, regular walking or mindfulness training can be as good as benzodiazepines. The AGS Alternatives List includes 47 evidence-backed non-drug options. These aren’t just ‘nice to have’ - they’re first-line recommendations.

Graham Holborn

Hi, I'm Caspian Osterholm, a pharmaceutical expert with a passion for writing about medication and diseases. Through years of experience in the industry, I've developed a comprehensive understanding of various medications and their impact on health. I enjoy researching and sharing my knowledge with others, aiming to inform and educate people on the importance of pharmaceuticals in managing and treating different health conditions. My ultimate goal is to help people make informed decisions about their health and well-being.