QT Prolongation Risk Calculator for Ondansetron

Patient Risk Assessment

Enter patient characteristics to determine risk level for ondansetron use.

Why Ondansetron Can Be Riskier Than You Think

Most people know ondansetron as the go-to drug for nausea after chemo or surgery. It works fast, it’s effective, and for years, doctors gave it without a second thought. But here’s the truth: ondansetron can mess with your heart’s rhythm - sometimes in dangerous ways. It doesn’t happen to everyone, but when it does, it can trigger a life-threatening arrhythmia called torsades de pointes. This isn’t theoretical. It’s documented. And it’s why hospitals changed their rules.

How Ondansetron Slows Down Your Heart’s Recovery

Your heart beats because of electrical signals. After each beat, it needs to recharge - that’s called repolarization. The QT interval on an ECG measures how long that takes. If it’s too long, your heart’s at risk for chaotic rhythms. Ondansetron blocks a specific potassium channel in heart cells (the hERG channel), which slows down that recharge. The result? A longer QT interval.

Studies show that a single 32 mg IV dose of ondansetron can stretch the QTc interval by up to 20 milliseconds. That’s not a tiny blip. That’s enough to cross into dangerous territory. Even an 8 mg IV dose can push it up by 6 ms. For someone already at risk - say, an older patient with heart failure or low potassium - that’s enough to tip them over the edge.

Who’s Most at Risk?

This isn’t a problem for healthy 25-year-olds getting nausea after a night out. The real danger is in people with existing vulnerabilities:

- People with congenital long QT syndrome

- Those with heart failure or slow heart rhythms

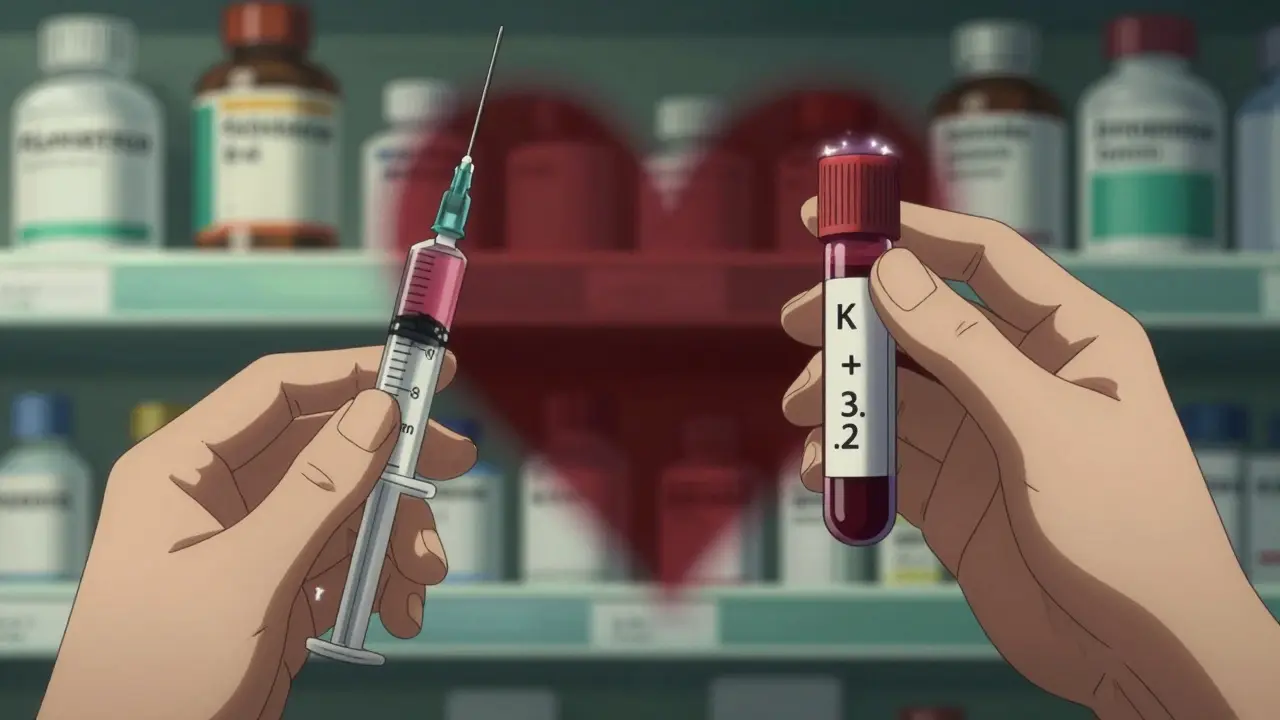

- Patients with low potassium or magnesium levels

- Anyone taking other QT-prolonging drugs (like certain antibiotics, antidepressants, or antifungals)

- Older adults - especially over 75

At Johns Hopkins, a 2019 case series found that 3 out of 15 elderly patients with preexisting heart conditions developed QTc intervals over 500 ms after a standard 8 mg IV dose. That’s a red flag. At that level, the risk of sudden cardiac arrest jumps sharply.

How Much Is Too Much?

The FDA stepped in back in 2012 after GlaxoSmithKline’s own testing showed the danger. They said: stop giving 32 mg IV doses. Never go above 16 mg in a single shot. But here’s the twist - even 16 mg is too much for some people.

Today, best practice in most hospitals is to cap IV ondansetron at 8 mg for high-risk patients. Oral doses are safer - up to 24 mg total in a day is generally okay because absorption is slower and less intense. But IV? That’s a direct hit to the bloodstream. No buffer. No warning.

One study in the Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice found that 42% of oncology nurses had seen ECG changes linked to ondansetron. 18% of those cases needed real intervention - like stopping the drug, giving magnesium, or calling a cardiologist.

Other Antiemetics - Are They Safer?

Ondansetron isn’t the only antiemetic with this problem. But it’s not the worst either.

Here’s how they stack up:

| Drug | Class | Max QTc Increase (ms) | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dolasetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 25-30 | High - FDA restricted use |

| Ondansetron (IV 16 mg) | 5-HT3 antagonist | 20 | High - avoid in high-risk |

| Ondansetron (IV 8 mg) | 5-HT3 antagonist | 6-10 | Moderate - use with caution |

| Granisetron (transdermal) | 5-HT3 antagonist | 3-5 | Low |

| Palonosetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 9.2 | Moderate - preferred in cardiac risk |

| Droperidol | Butyrophenone | 15-20 | High - requires ECG monitoring |

| Prochlorperazine | Phenothiazine | 10-15 | Moderate |

Palonosetron is now the preferred choice in many oncology centers for patients with heart issues. It’s just as good at stopping nausea, but it doesn’t stretch the QT interval nearly as much. Granisetron patches are even safer - no IV, no spike, no risk.

What Hospitals Are Doing Now

Since the FDA warning, things have changed. In 2011, only 37% of U.S. hospitals had protocols for monitoring ondansetron. By 2022, that jumped to 92%.

Here’s what a typical modern protocol looks like:

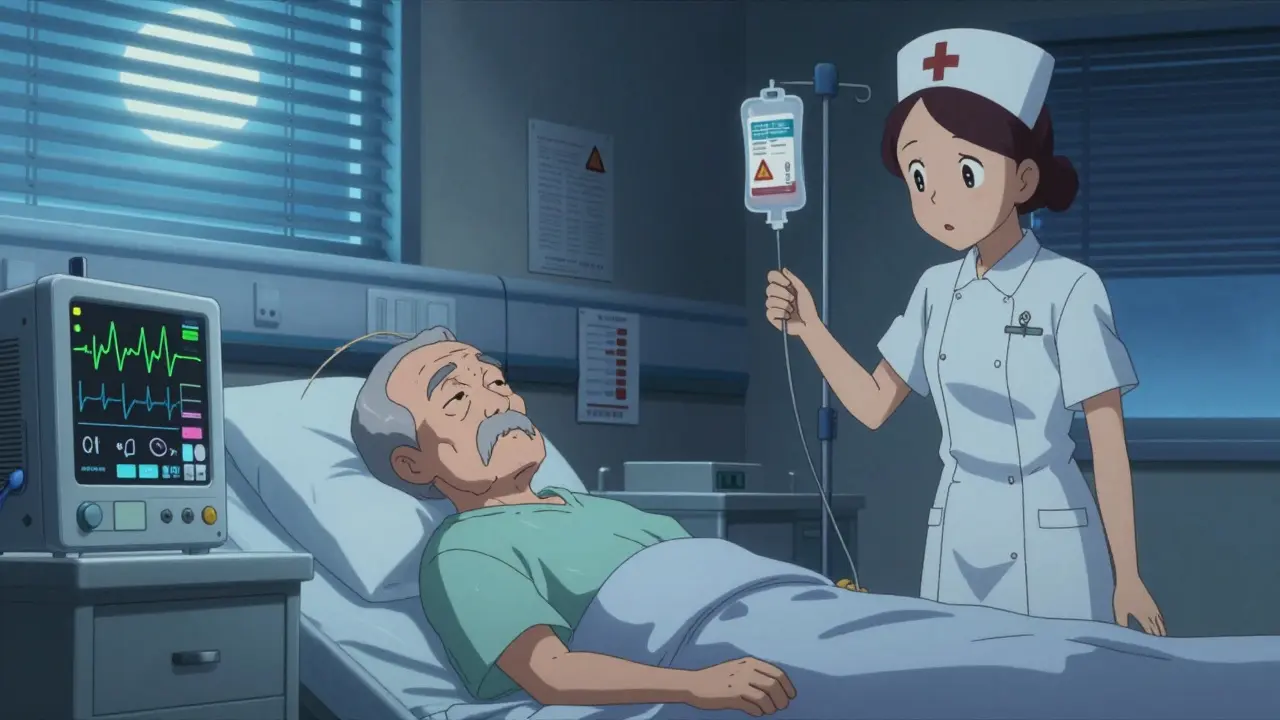

- Check baseline ECG if patient has heart disease, electrolyte issues, or is over 65.

- Correct potassium below 3.5 mEq/L or magnesium below 1.8 mg/dL before giving IV ondansetron.

- Limit IV dose to 8 mg for high-risk patients. Never exceed 16 mg.

- Consider alternatives like dexamethasone or aprepitant for low-risk nausea.

- Monitor ECG for 4 hours after IV dose if QTc was over 440 ms at baseline.

At Massachusetts General, one ER doctor switched to dexamethasone alone for low-risk nausea after seeing QTc spikes in heart failure patients. No ondansetron. No risk. And the nausea still went away.

What You Should Ask Your Doctor

If you’re about to get ondansetron - especially by IV - here’s what to ask:

- Is this the lowest effective dose?

- Have you checked my electrolytes?

- Do I have any heart conditions or take other drugs that affect QT?

- Is there a safer alternative?

- Will I need an ECG before or after?

Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s common. If you’re older, have heart problems, or take other meds, your risk is real. Push for answers.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Ondansetron is still the most prescribed antiemetic in the U.S. - over 18 million prescriptions in 2022. But IV use has dropped 22% since 2012. Why? Because doctors learned. Nurses learned. Pharmacist teams now verify QTc calculations before high doses are given.

The FDA has logged 142 cases of torsades de pointes linked to ondansetron between 2012 and 2022. Almost all involved doses over 16 mg. That’s preventable. That’s avoidable.

And it’s not just about ondansetron. This is a lesson in how a drug can be both highly effective and quietly dangerous. We used to think nausea was the only problem. Now we know - the heart can pay the price.

What’s Next?

Researchers are now looking at genetics. Some people metabolize ondansetron slowly because of their CYP2D6 gene - and that makes the QT effect worse. A major NIH trial called QT-EMETIC is testing whether tailoring doses based on genetics can reduce risk. Results are expected in mid-2024.

For now, the message is clear: use ondansetron wisely. Don’t default to the highest dose. Check the ECG. Fix the electrolytes. Consider alternatives. Your heart will thank you.

Graham Holborn

Hi, I'm Caspian Osterholm, a pharmaceutical expert with a passion for writing about medication and diseases. Through years of experience in the industry, I've developed a comprehensive understanding of various medications and their impact on health. I enjoy researching and sharing my knowledge with others, aiming to inform and educate people on the importance of pharmaceuticals in managing and treating different health conditions. My ultimate goal is to help people make informed decisions about their health and well-being.